Major literary figures were active during the fin de siecle, but their oeuvres were rooted in the Naturalism which came before it. They certainly don’t embody the Modernism of its aftermath in any meaningful way. Meanwhile, the fin de siecle authors mentioned above and their contemporaries are either shoehorned into these two broad periods or positioned as odd residual bursts of Romanticism.

I find neither treatment satisfying. There is a yawning chasm between Naturalism’s journalistic slice of life and the iconoclasm and alienation of Modernism. Further, anyone who’s seen a Monet and a Picasso knows a massive disruption and evolution must have occurred in the arts at the very end of the 19th Century, particularly in France. This revolution cannot be explained merely by Naturalism falling out of fashion. It requires an intermediate step, a transition.

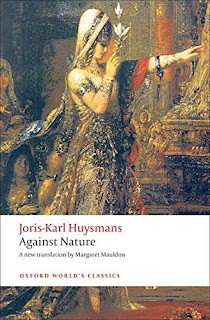

Cards on the table; I have no qualifications. I’m neither a scholar of French literature nor an expert in French history. What I am is a life-long avid reader of literature, with an especial love of French literature and art. A few years ago, I was reading works by gay authors of the Belle Epoque, such as Andre Gide, Constantine Cavafy, Marcel Proust (didn’t quite acquire the taste), and Thomas Mann. This led to me encountering dandyism, which necessarily led to J.-K. Huysmans’ novel A rebours (Against Nature or Against the Grain). This novel is credited with launching the Decadent movement in literature and is often referred to as its bible. I read the Oxford translation pictured.

A rebours is a strange novel. Huysmans was a disciple of Naturalist master Emile Zola, but A rebours is clearly not a Naturalistic work. Zola repudiated it. Black and cynical, replete with alienation and disgust, and offering only a rudimentary plot while it focuses on its antihero’s interior psychology, A rebours has many Modernist traits. However, it was written in 1884. That’s way before Modernism existed, and its style is far too ornate and lush for Modernism. In short, it belongs to neither Naturalism nor Modernism. It’s something in-between, and it’s far too accomplished and intentional to be dismissed as an unconscious mongrel.

I was fascinated by A rebours's style, themes, perspective, and sense of life. After checking out an excellent anthology of French Decadent short fiction by Oxford Press (French Decadent Tales), I dove deep into French Decadent fiction. Years later, after having read a couple dozen novels and short story collections, I remain fascinated. The French Decadents bended and twisted prior literary movements through the prism of their own innovations, concerns, and perspectives, creating something distinct and setting the stage for true Modernism in the 20th Century. I find myself agreeing with those who suggest Decadent literature does (and must) form a discrete literary period.

Often frustrated by the lack of resources treating Decadence as anything more than an aberrant literary sideline, I'm creating this blog to share my reactions to the movement’s works. There must be other people with a similar interest since publishers such as Snuggly Books, Dedalus, and Wakefield actively produce English translations of Decadent fiction.

Let’s begin!

I wonder if Gustave Flaubert can (or is?) considered as a precursor in spirit to the French decadent writers, especially because he despised and satirizied and mocked the bourgeoisie in Madame Bovary (1857). And Flaubert's novel Salammbô (1862) alternates between scenes of violent excess and brutality in the Punic wars and extended and very detailed descriptions of the wealth, food, fashion, architecture of ancient Carthage, which Flaubert seems to admire and relish writing about.

ReplyDeleteFrom the reading I've done so far, he seems to be classified as an influence on the Decadents. His style, as with many Naturalists, was to present a slice-of-life. That often meant focusing on seedy or amoral elements in society. This focus arose for many reasons including: a direct reaction against the heroic idealism of Romanticism, the need to 'tell it like it is' rather than polite, and to brutally expose social or economic injustice. My feeling is Flaubert was not a Decadent (and I wonder whether he would have approved of the movement). The similarities you mention (and which can be seen in anti-Decadent Emile Zola's novels, as well) are there not because he was a Decadent but because Decadent writers were inspired by his approach. Of course, they used it to accomplish very different ends! Just my opinion though.

ReplyDelete